Embracing the Full Catastrophe

Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.

No text has had a greater influence on my life than the 1990 book Full Catastrophe Living by Jon Kabat-Zinn. It’s an early, seminal self-help book detailing the values of mindfulness and meditation in the face of stress, anxiety, and chronic pain. While I had already been practicing meditation prior to reading the book, what really stuck with me was the eponymous idea of “The Full Catastrophe.”

Taken from a line of dialogue in Zorba the Greek, Kabat-Zinn’s use of the full catastrophe is essentially a reflection of the idea that a life fully lived is one that will inevitably experience both the highest of highs and the lowest of lows. In the associated film, Zorba uses this phrase in the context of being asked if he is married. He responds, “Am I not a man? And is not a man stupid? I’m a man. So, I’m married. Wife, children, house – everything. The full catastrophe.” For Zorba, this is not a wholly negative statement, but rather an acceptance that there is no such thing as a life without suffering. While it may seem like a simple idea, I’ve benefited greatly from it.

Understanding the full catastrophe concept can help one live a more full life. The inverse of that is true as well. The default mode for many individuals is to live one’s life attempting to minimize the likelihood of experiencing low lows. I’ll give an example from my work coaching to make this more salient.

I’m currently gearing up for recruiting season with DiG and Glory (my two Boston-based teams). In recruiting calls, I talk to many young players who are right at the cusp of being talented enough to make one of my teams, but are in no way guaranteed a roster spot. And even if they were to make the team, they’d likely be towards the bottom of the roster, with limited opportunities for playing time. This prospect consistently elicits what I see as a negative reaction.

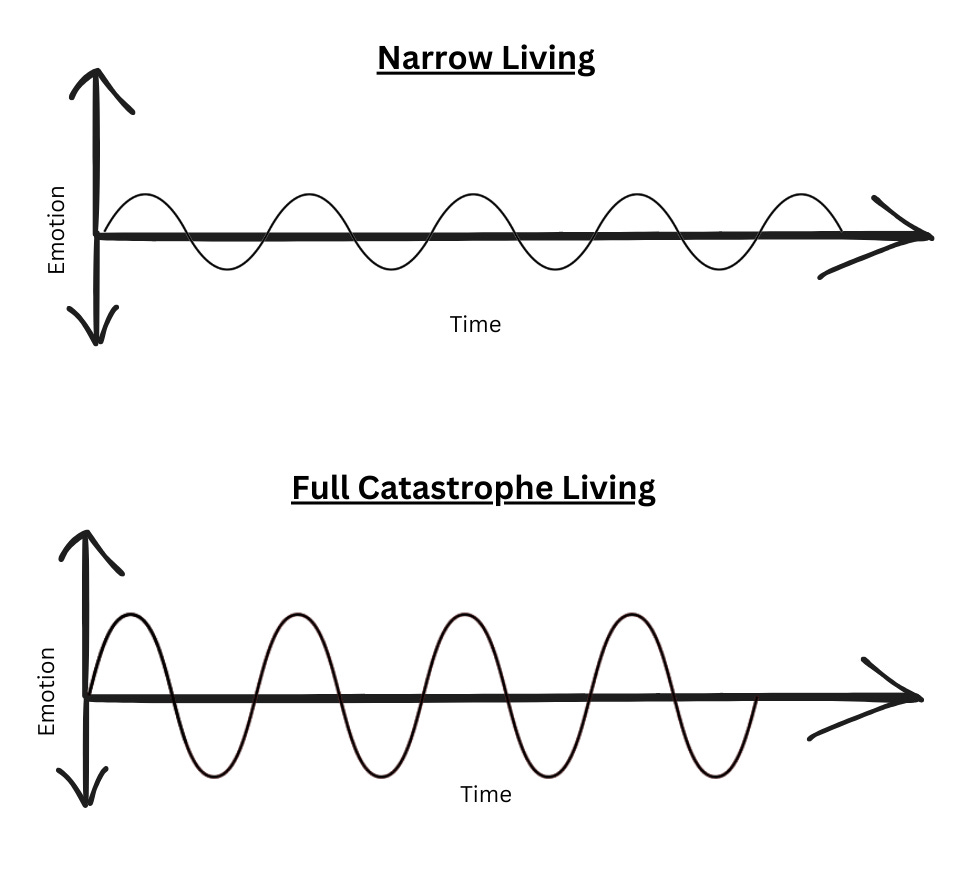

The fear of failure prevents the player from even trying out for the team in the first place. Why? The player imagines the negative emotion they’ll feel being cut from the team or going to a tournament and not getting any playing time. Because of how scary that can feel, it’s much easier to insulate oneself from that potential negative experience and stick with what’s comfortable – like playing for a less competitive team they know they’ll have a roster spot on. Of course, this self-preservation instinct comes with a major drawback. In shying away from potentially negative experiences, individuals end up flattening the spectrum of experiences they can have – including positive ones. This is what I call “narrowing the aperture of experience.” While you protect yourself from some of the low lows, you’re also going to miss out on the high highs that can only come from achieving something that comes with great risk of failure.

As illustrated above, the second approach to life is the one that I think is most worth embracing. Full catastrophe living widens the aperture of experience. It’s a life where more risks are taken. It’s a life where, when faced with a decision that could go really well or really bad, you lean in and take that leap of faith. A life where the fear of failure does lead to inaction. Full catastrophe living opens yourself up to the full spectrum of human emotions – the highest of highs and lowest of lows. In the above example, it’d mean trying out for the team because it’s scary.

Finally, the magic of embracing this approach to life is that, in consciously operating in this way, the lows become more manageable. Why is this the case? In my personal experience, it’s because I realize that the things that hurt most acutely stem from failure in a domain I care deeply about. For example, losing in the quarterfinals of Club Nationals felt terrible, but as I reflected on why it hurt so much, I felt a deep sense of gratitude for having something I felt so passionate about that it brought me to tears when we fell short of our goals. In this reflection, I am reminded of the famous Tennyson quote, “Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.” That’s the full catastrophe experience.

Loved this one!

Question: Are there any heuristics you use to distinguish between lows that are in service of growth (or the consequence of taking a justified risk!) and lows that are just...bad.

It seems to me like some kinds of suffering truly are part of a full life (say, mourning the loss of a loved one), while others really only detract (say, chronic pain or severe mental illness).

Do you think about it the same way, or is there another frame you use?